The Study of Personality

ZILLO Young Reporter Jack Bojtler, Takes us on a deep dive into ‘The study of personality’

Psychology, as a field of study, is relatively recent compared to other academic disciplines (emerging with the creation of Wundt’s laboratory - 1879) and consequentially, we still do not have an entirely comprehensive understanding of the complexity of human behaviour, one aspect of this being personality. This, combined with the nature of the human brain being a learning machine of unparalleled intricacy; made up of approximately 86 billion neurones that are constantly rewiring themselves into new nervous pathways, underscores the complexity of human personality, portraying all of the insights we are yet to discover within this field of psychological exploration.

Despite this, milestones such as the cognitive revolution of the 1950s and the emergence of neuroscience as a prominent field of study have propelled our understanding of the human brain and its intricate workings. Furthermore, advancements in neuroimaging technology, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG), have provided researchers with unprecedented insights into the neural correlates of behaviour and personality traits. This, in addition to continuous refinement and expansion on psychological theories, has now enabled us to understand personality on environmental, biological and psychological levels of analysis.

This article will focus on the three aforementioned personality measurement tools: the MBTI (focusing on 4 dichotomies of personality) the big 5 (a more scientifically valid development on the MBTI) and the enneagram (regarded by many as a pseudoscience but equally still has some use towards self-improvement and comprehension of our own identity). We will examine each of these frameworks in detail and explore how they can provide valuable insights into our neurochemical and biological makeup, ultimately informing our understanding of ourselves and guiding personal development efforts.

If you would like to determine your personality type prior to or after reading this article, you can try any number of the following free tests:

The MBTI (Myers-Briggs Type indicator)

The MBTI, Also known as the 16 personalities test, allocates individuals into one of 16 personality types with a 4 letter type. This is based on 4 dichotomies: Introversion/Extraversion, Sensing/Intuition, Feeling/Thinking and Perceiving/Judging. These dichotomies were first suggested by psychologist Carl Jung and later expanded upon by Isabel Briggs Myers and Katherine Cook Briggs; hence its name, and was the most scientifically valid personality measurement tool prior to the creation of the Big-5 test. Let’s delve into each of these traits, how to tell which most applies to you and their neurobiological basis.

Introvert (I) Vs Extrovert (E)

Typically, we assume that individuals who are confident, talk more frequently and are more bubbly in their nature are extroverted, while those who are more reserved, shy and less talkative are introverts. However, this is not necessarily the case, as it is not always truly possible to discern this based solely off of observed social behaviour, as there are many cofounding variables at play, such as cognitive processing within individuals, neurodivergency and social demands.

There are many fundamental variations between introverted and extroverted individuals. One of which is their social battery, meaning the extent to which they can socialise before becoming socially drained and therefore requiring time in solitude to socially recharge. Sensitivity to the neurotransmitter dopamine - the molecule related to pleasure, motivation etc. – is a driving force for this. The lower an individual’s extraversion is, the less time they can spend socialising before the feeling of becoming socially drained ensues, and vice versa.

As a consequence of this, both the frequency of socialisation and the extent of the group size when an individual socialises may be indicative factors for levels of extraversion, as this will result in a significantly higher influx of dopamine release in the brain. Furthermore, some other noticeable differences in cognition between introverted and extroverted individuals lies in thinking patterns and processing; extroverted individuals being more accustomed towards rapid responses and quick processing, due to a preference toward use of the dopamine pathway, while introverted individuals favour processing information more slowly and deeply, leaning towards the acetylcholine pathway (though these pathways are theoretical explanations and not universally accepted by all researchers). In addition, it is theorised that extroverted individuals are by nature more externally focused; as opposed to the internal focus of introverted individuals toward their inner world, thoughts and feelings.

Therefore, the amount of time you spend socialising compared to in solitude and your preferred group size, can be beneficial for determining whether you are more of an introverted or extroverted individual. Perhaps, try socialising more or less than you typically would in your average day in environments of varied stimulation levels and reflect on your subsequent energy levels. It takes time to gauge your optimal level of interaction, but once you begin to develop an awareness of this, it can be instrumental in determining how to structure your day and a plethora of other applications. If you are aiming to develop a sense of adaptability on a social basis, practise getting more comfortable with solitude or being with others, depending on your individual level of extraversion. Working to make yourself as comfortable as possible in both of these environments has the potential to greatly empower yourself not only now, but especially in the future.

Summary: Introverted = lower social battery/smaller social group size, extroverted = greater social battery/larger social group size

Sensing (S) Vs Intuition (N)

The dichotomy between sensing and intuition refers to the internal processing of the world around us, whether by relying on our five senses, reality, statistics and pragmatism (sensing) or by recognising patterns, associations, drawing connections and a preference for abstraction (intuition). Interestingly, it is estimated that 70% of all humans are sensing rather than intuitive. From an evolutionary standpoint, this would be explained by the need for having less individuals to forge new paths and make new discoveries in society, while it would be beneficial for the majority to stick to what has already been learned, rather than the unknown. Too many intuitive individuals, and society would not be able to effectively apply learned knowledge and make subsequent developments; while too many sensors would result in a less rapid rate of development and discoveries. Therefore, the 70/30 ratio does have significant evolutionary backing.

Generally speaking, it is suggested by the MBTI sensors and intuitives have a psychological preference for engaging with those of the same type. The fundamental reason for this is that topics of conversation and activities that will energise each respective type will drain the other. We can see this in conversation as one aspect. Sensors will have a preference towards talking about events from their own and others lives and other topics grounded in reality, potentially deeming theoretical discourse as being an inadequate use of time due to a lack of grounding in reality, while intuitives will lean towards abstract and conceptual topics of conversation, deeming small talk and conversation centred around day to day life as holding less value than the unexplored and unknown.

A key supporting study to this is "Personality Similarity and Relationship Satisfaction in Dyadic Interactions: A Meta-Analysis" (Luo & Klohnen, 2005) which explored how personality similarity influences relationship satisfaction in dyadic interactions. Findings revealed that individuals, particularly sensors and intuitives, prefer interacting with others who share their cognitive processing style. Sensors reported greater satisfaction with fellow sensors due to shared interests and a focus on practicality, while intuitives found satisfaction with other intuitives through abstract discussions and exploration of the unknown. Thus, underscoring the importance of cognitive compatibility, particularly between sensors and intuitive, in fostering harmonious interactions and relationship satisfaction. This suggests that individuals tend to gravitate towards others who share their cognitive preferences, emphasising the significance of understanding one's own sensing or intuitive tendencies in social dynamics.

If you are more sensing, you may find working on imaginative and abstract thinking may be of great value in this aspect of personality, while for intuitives, practising living in the moment and making your ideas tangible, working to make them a reality, can be equally beneficial.

Summary: sensing = focus on facts/reality/what is known/practicality, intuitive = focus on the abstract/imagination/the unknown/theorising

Thinking (T) Vs Feeling (F)

This dichotomy delves into differences in the decision making of individuals. If an individual is more feeling, they will have a greater tendency to lean towards how they and/or others feel, as opposed to a thinker, who will have a preference towards objectivity over subjectivity, prioritising logic and truth over the emotions of others and themselves. Therefore, feelers may be positively regarded for their empathetic abilities, understanding and awareness of the needs of themselves and those around them, though they may face difficulties in maintaining objectivity and making decisions based solely on logic and rationality. They may prioritise the emotional needs of themselves and others to the extent that they neglect practical considerations or overlook potential consequences. This can lead to decision-making biases, such as favouring personal relationships over merit or avoiding necessary confrontations to preserve harmony. Additionally, feelers may find difficulty in setting boundaries and asserting themselves in situations where their values or emotions are at odds with others'.

On the other hand, thinkers find natural proficiency in maintaining objectivity, emotional regulation and boundaries with others. However they may experience frustration with acknowledging and expressing emotions, both in themselves and others, prioritising logic and reason to the extent that they overlook or suppress emotional considerations. This can lead to interpersonal difficulties, as others may perceive thinkers as cold, insensitive, or overly analytical. Additionally, thinkers may find it challenging to navigate situations that require empathy, compassion, or understanding of complex emotional dynamics.

Regarding the underlying biological processes of thinking and feeling, it may be the case that, although not addressed in the framework of the MBTI, that there is both influence on a neurobiological and neurological level. Neuroscientific research has identified brain areas associated with cognitive and emotional processing. For example, thinking processes are often associated with regions of the prefrontal cortex, which are involved in logical reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving. Feeling processes, on the other hand, are associated with limbic system structures like the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, which play roles in emotional processing and empathy. In conjunction to this, thinking-oriented individuals may exhibit differences in dopamine and serotonin activity, in comparison to feeling-oriented individuals. Dopamine, often associated with reward and motivation, may play a role in facilitating logical reasoning and cognitive processing, while serotonin, known for its role in mood regulation, may impact emotional responses and social behaviours associated with feeling preferences.

By recognising and understanding these challenges, individuals can strive to balance and integrate both thinking and feeling aspects of their personality, leading to more effective decision-making and interpersonal relationships.

Summary: feeling = decision making grounded by emotional and social factors, thinking = decision making favouring logic and objectivity.

Judging (J) Vs Perceiving (P)

The final dichotomy of the MBTI focuses on organisational variations within individuals, such as one’s relationship with structure and flexibility when it comes to routine. For perceiving individuals, they have a preference towards flexibility of schedule, and may feel that they are choked out by a consistent daily routine; potentially seeing it more as something of a nuisance as opposed to a catalyst to their day-to-day life. Their spontaneity and flexibility can be both a blessing and a curse, as it can result in being open to more of the possibilities of life and new experiences, while, on the other hand, it can result in difficulties regarding decisiveness, organisation and consistency. Opposing this is the relationship Judgers have with structure and routine.

Typically, judging individuals will view routine as an essential tool and find comfort in planning and order in their lives. They possess rapid abilities of discernment and stick with a task or decision. Despite this, these decisions are often made with improper contemplation on information too quickly. Furthermore, the rigidity of judging individual’s routine can be detrimental to themselves and the opportunities in their lives – likely leading to the individual being consumed by their organisation.

Regardless of your type, aspiring towards an organisational equilibrium can yield benefits in many aspects within life – essentially, creating a more holistic work-life balance, thus ensuring you do not get consumed in either. Maintaining organisation, without walling yourself off to the opportunities and new experiences within life may prove invaluable, granting you new pathways in life while still being able to independently navigate them. As you may see as a recurring trend throughout all of these dichotomies, creating a sense of harmoniousness is one of the fundamental keys to unlocking your capacity for achievement and fulfilment in life.

Summary: judging = organised/prefer routine/structured way of life, perceiving = flexible/less focus on routine/spontaneous

Cognitive functions

Depending on your personality type, you may find that the operation of your thinking/feeling may differentiate to that with others, as is the case for sensing and intuition. Carl Jung explains this in his theory of cognitive functions, which states that sensing, intuition, thinking and feeling are either introverted or extroverted, and are each at different levels of proficiency and usage depending on personality type. This, known as a functions stack, is a hierarchy following the order of dominant (most proficient and used), auxiliary, tertiary and inferior (least proficient and used). For instance, these are the order of my cognitive functions as an INFJ:

Dominant: Introverted Intuition (Ni) – Most accessible and developed cognitive function of INFJs. Thus, searching for deeper meaning, patterns, trends, symbolism and the connections between these comes naturally. Resulting in a preference to explore a particular topic in great depth, rather than continuously jumping from one idea to another and exploring all potential possibilities.

Auxiliary: Extroverted Feeling (Fe) - prioritises social harmony and the emotional needs of others, prioritising the perspectives of others to make an informed decision.

Tertiary: Introverted Thinking (Ti) – gives a sense of logical grounding and equilibrium to Fe, ensuring that emotionality does not completely consume decision making.

Inferior: Extroverted Sensing (Se) – the least developed of an INFJ’s cognitive functions, responsible for responding to the external environment. Thus, it may consequentially result in sensory sensitivity, impulsiveness and losing touch with the details of reality, thereby struggling to anchor Ni.

The antithesis to this order of functions would be that of an ISTJ, due to the juxtaposing sensing and thinking, as opposed to intuition and feeling:

Dominant: Introverted Sensing (Si) – The ISTJ’s dominant function enables the vivid depictions of experiences within their lives and navigating learned information with ease in a systematic and strategic manner.

Auxiliary: Extroverted Thinking (Te) - manifests as a structured, logical approach to decision-making and problem-solving, prioritising efficiency, organisation, and clear communication based on facts and evidence.

Tertiary: Introverted Feeling (Fi) – Focuses on values and morality on the individual to make decisions – adding a dimension of emotional backing to the ISTJ’s Te.

Inferior: Extroverted Intuition (Ne) – The ISTJs weakest function can manifest in a lack of openness to new ideas and innovation and a preference for familiarity and routine due to the overriding dominance of Si.

Understanding and strengthening cognitive functions can significantly enhance personal growth, self-awareness, and overall well-being. Through a conscious understanding of the unique role each function plays in shaping our thoughts and behaviours, we enable ourselves to navigate life's complexities with greater clarity and purpose. Methods including engagement in mindfulness practices, seeking feedback, and intentionally developing weaker functions are powerful strategies for developing a sense of harmony and balance within our cognitive functions.

The Big-5: A more thorough and reliable approach, characterised by empiricism.

Although the MBTI is one of the most widely used personality assessments throughout many areas of modern day society, ranging from workplace environments to being a casual topic of conversation, there are a tremendous amount of concerns regarding its limitations. However, as our understanding of the features of personality have developed since the creation of the MBTI, along with our uncertainty of its validity, the MBTI has been deemed to be obsolete, and the Big-5 (OCEAN) has come to be.

Characterised by dimensionality

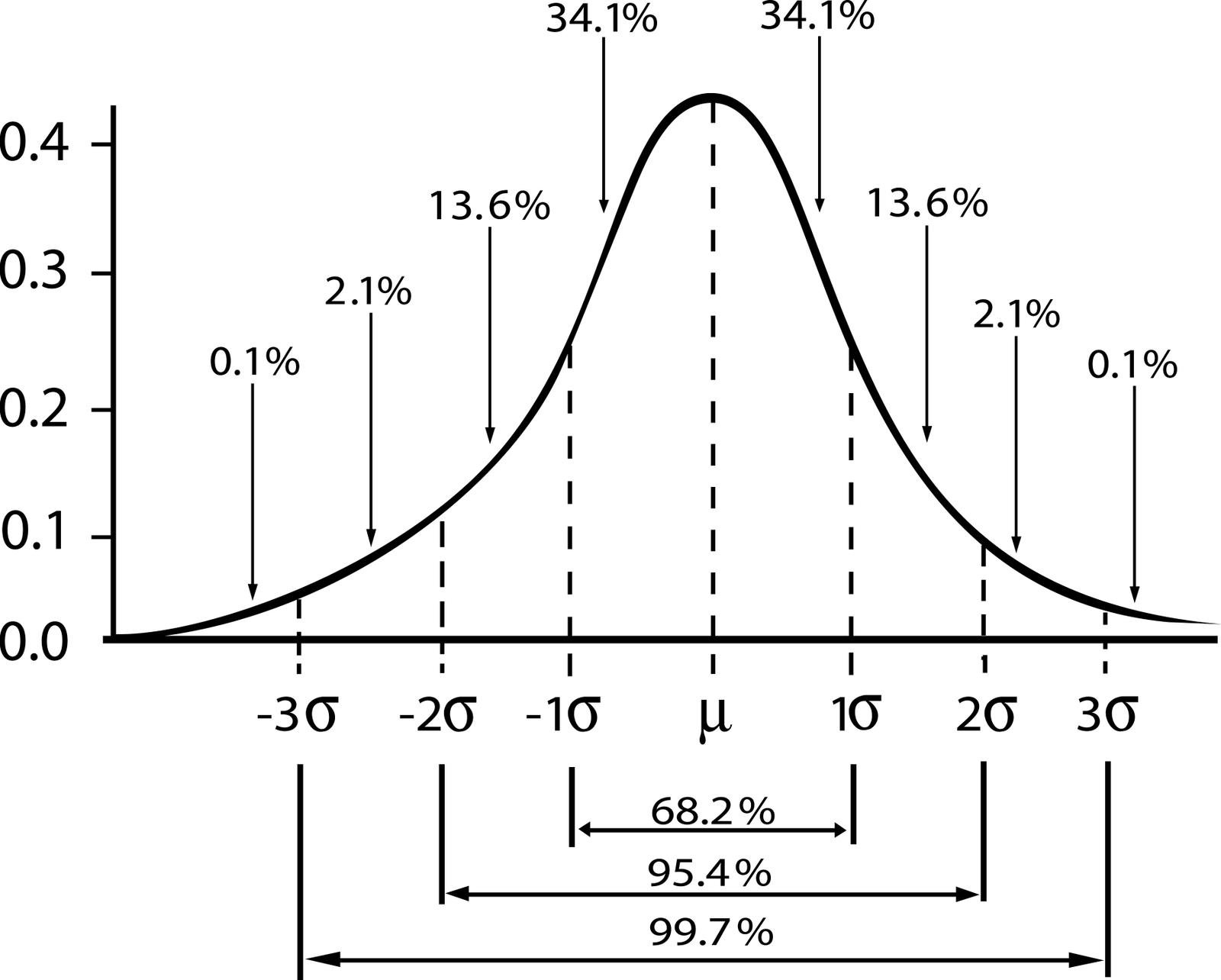

The nature of the Myers-Briggs being based upon dichotomies is highly reductionist and does not give justice to the complexity of personality; attempting to categorise us into one of 16 types, adopting a binary nature to human personality. However, we have now come to learn that this is not representative of human behaviour, as dimensions of personality lie along a bell shaped curve, suggesting limited validity. I shall use extraversion as an example of this, as this is a feature of both the MBTI and the Big-5, while the other measures I will explain (besides neuroticism) can fundamentally be viewed as derivatives of the traits the MBTI describes.

As our understanding of the nature of extraversion has increased via psychological research over time, it has now become apparent that the majority of individuals are not simply introverts or extroverts as the MBTI suggests, but instead fall in-between these measures as ambiverts (68%). Levels of extraversion of the human population are distributed across a bell shaped curve, being of the same nature as an IQ graph (though this measure has its own issues, and will be covered in a later article on human intelligence). As previously mentioned, 68.2% of individuals fall between two standard deviations (-1 to 1) of the average extraversion level, followed by 27.2% +/- 1-2, 4.2% +/- 2-3 and 0.2% +/- 3-4. This finding also applies to the derivative personality aspects of the Big-5. Consequently, it is evident that the MBTI is not only highly reductionist, but additionally suffers from low validity by incorrectly measuring what it attempts to measure, therefore having limited explanatory power regarding personality.

Contrastingly, the Big-5 utilises the groundwork laid out by the MBTI and separates the wheat from the chaff, having dimensions that are significantly higher in validity due to being backed by psychological theories and research, in addition to higher reliability due to consistency of individual’s results, as opposed to the MBTI’s limitations. Rather than the use of dichotomies, the Big-5 traits lie along a continuum from low to high and gives the individual taking the test a result that is far more comprehensive by giving a score/percentile, as previously explained with the use of extraversion as an example.

Theoretically supported

A fundamental limitation to the MBTI is that the traits it measures are unconscious concepts and thus cannot be truly and accurately measured, while the big-5 describes personality traits that can be observed in human behaviour and conversely are able to be measured through scientific and empirical methods of experimentation. The dimensions of personality measured by the big-5 additionally have their own sub-dimensions, all of which have been extensively researched, henceforth enabling a more accurate and objective representation of human behaviour. This is not to say that the MBTI is entirely invalid in what it describes, as there is a case to be made for the fact that we are able to understand these unconscious processes to an extent, but in regards to the objective and empirical measurement of human behaviour, the Big-5 is certainly empirically backed and overall a more comprehensive approach for objectively measuring human behaviour.

The Big-5 traits (OCEAN)

Openness to experience

This aspect of the big-5 is synonymous with the dichotomy of sensing/intuition and encompasses a broad range of characteristics describing the degree to which an individual can be described as possessing traits that revolve around imagination, curiosity etc. as opposed to the MBTI’s focus on unconscious informational processing. Regarding the neural correlates of openness, Colin G. DeYoung (2010) found associations with the default mode network (activated when the mind is in a wandering/rest state) and increased size in the prefrontal cortex (responsible for higher-order thought processes, referred to as executive functions).

The sub-dimensions it is comprised of involve imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, intellectual curiosity and psychological liberalism.

High Openness to experience: imaginative, creative, philosophical, curious, artistic, introspective, inquisitive, non-conformist.

Low Openness to experience: traditional, dislike of change, Inflexible, resists new ideas, conformist.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness draws from the Judging/Perceiving dichotomy, though it emphasises organisation, diligence, and reliability more comprehensively. "The Role of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in the Regulation of Task Performance: A Dual-Task Investigation" by Todd S. Braver et al. (2001) provided insights into the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in executive functions, which is associated with conscientious behaviour (planning, working memory, inhibition etc.).

Conscientiousness is comprised of the sub-traits of cautiousness, self-efficacy, orderliness, dutifulness, achievement striving and self-discipline.

High Conscientiousness: organised, diligent, reliable, responsible, punctual, goal-orientated.

Low Conscientiousness: disorganised, careless, impulsive, irresponsible, inconsistent, procrastinates.

Extraversion

Fundamentally, the big-5 and the MBTI share the same core framework in regards to extraversion; encapsulating characteristics such as sociability, assertiveness, and positive emotionality. Scholarship such as "Extraversion and Reward-Related Processing: Probing Incentive Motivation in Emotional Expression and Psychopathology" by Robert E. Rydell et al. (2010) underscores the interplay of reward-related processing mechanisms in extraverted individuals.

Extraversion involves 6 sub-facets: gregariousness, assertiveness, warmth, activity level, excitement-seeking and positive emotions.

High Extraversion: energetic, assertive, optimistic, expressive, assertive, risk-seeking, sociable, enjoys attention.

Low Extraversion: reserved, reflective, calm, introspective, independent, thoughtful, risk-averse, avoids attention.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness, reflecting facets of the Thinking/Feeling dichotomy, centring away from the extent to which individuals rely on either emotionality or logic for decision making abilities, instead, focusing on traits associated with cooperation, empathy, and compassion (in essence the tendency of an individual to prioritise the needs of others over themselves). "The Neural Basis of Human Social Values: Evidence from Functional MRI" by Fumiko Hoeft et al. (2011) is one instance of a study that has brought to light the involvement of cerebral regions such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in processing social values, a constituent of agreeableness.

Its sub dimensions are comprised of trust, morality, altruism, cooperation, modesty and sympathy.

High Agreeableness: empathetic, compassionate, forgiving, accommodating, warm, sincere, humble, polite.

Low Agreeableness: competitive, sceptical, blunt, critical, straightforward, insincere.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism is arguably the only dimension within the big-5 that cannot be related to any of the dichotomies presented by the MBTI, focusing on the propensity of an individual to experience negative emotion. The psychological study “Amygdala Volume and Social Network Size in Humans" by Bickart et al. (2010) found that individuals with larger amygdala volumes tended to have larger and more complex social networks. Additionally, they observed that neuroticism was negatively correlated with amygdala volume, suggesting that lower amygdala volume may be associated with higher levels of neuroticism.

Neuroticism consists of anxiety, anger, depression, self-consciousness, immoderation and vulnerability.

High neuroticism: anxious, sensitive, nervous, pessimistic, reactive, self-conscious.

Low neuroticism: calm, stable, optimistic, robust, confident, easy-going, steady, secure.

Evaluating the Big-5

Despite its strengths and improvements upon the MBTI, the big-5 is not without its critiques, as some argue that human personality is overall, simply too complex to be reduced to simply 5 dimensions, therefore deeming the big-5 to be reductionist in its explanation of human behaviour. In addition to this, as with all questionnaire style self-testing methods, the big-5 suffers from response bias. For instance, a disagreeable individual may want to appear more agreeable than they actually are, and therefore inaccurately rate themselves in a more favourable manner, while individuals who have a disproportionate sense of self-esteem (inaccurately high or low) may answer in such a way that is reflective of this. Henceforth, the self-assessment method of questionnaires to give individuals their big-5 traits is another limitation to the big-5, though a potential resolving implementation could be the presence of an experimenter within the room.

In spite of this, 5-factor models such as the Big-5 are the current most scientifically supported, valid and reliable personality measurement systems that we currently have at our disposal. One of the key strengths of the Big Five personality traits is its extensive empirical support, backed by numerous studies conducted across different populations and cultures, giving high external validity in the form of cultural validity. An example of a study supporting the Big Five model is the research conducted by Costa and McCrae in the 1980s and 1990s. Costa and McCrae conducted a series of longitudinal studies using large samples of participants to explore the stability and validity of the Big Five personality traits over time. One of their landmark studies, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 1980, involved assessing over 1,000 adult participants using a comprehensive personality inventory known as the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI). Through their research, Costa and McCrae found strong evidence for the stability of the Big Five traits across different age groups and life stages. They observed that individuals tended to maintain consistent personality profiles over periods ranging from several years to decades, indicating the enduring nature of personality traits. The findings from Costa and McCrae's research, along with subsequent studies by other researchers, provided robust empirical support for the Big Five model's reliability, validity, and cross-cultural applicability. These studies contributed to the widespread acceptance of the Big Five framework as a valuable tool for understanding and assessing personality traits in diverse populations. Overall, the empirical evidence derived from longitudinal studies, cross-sectional surveys, and meta-analytic reviews has consistently reaffirmed the utility and validity of the Big Five personality traits, reinforcing its status as a foundational model in personality psychology.

The enneagram

Diverging away from the somewhat similar constructs of the MBTI and the Big-5 is the Enneagram, a personality typing system that delineates nine interconnected personality types, each characterised by distinct motivations, fears, desires, and behavioural patterns. This model posits that individuals predominantly embody one of these nine types, influencing their worldview, interpersonal dynamics, and personal growth trajectory. Each type has two respective wings based on its positional counterpart on the enneagram, for instance, type 4s will either be 4w3 or 4w5 based on which is more prominent in their personality. Furthermore, another fundamental aspect to the enneagram is an individual’s tritype, a combination created by dividing the enneagram into gut (8,9,1) heart (2,3,4) and mind (5,6,7) and creating a three digit code based on the most prominent of each (For me, this is 2w1 259). Rooted in ancient spiritual traditions, but adapted for contemporary psychological use, the Enneagram offers an unorthodox approach towards human nature and behaviour.

1 - The Reformer:

Individuals embodying this type strive for perfection and adhere to strict moral and ethical standards. They are principled, organised, and self-disciplined, often seeking to improve themselves and the world around them. However, they may become overly critical of themselves and others, grappling with feelings of resentment and frustration when their expectations are not met.

2 - The Helper:

Type Two individuals are compassionate, nurturing, and altruistic, driven by a desire to assist and support others. They thrive on forming meaningful connections and often prioritise the needs of others above their own. However, they may struggle with boundary-setting and experience resentment or martyrdom when their efforts go unacknowledged or unreciprocated.

3 - The Achiever:

Individuals of this type are ambitious, success-oriented, and image-conscious. They excel in goal-setting and productivity, often striving for recognition, admiration, and external validation. While they are adept at achieving their objectives, they may struggle with authenticity and self-worth, feeling empty or disconnected from their true selves amidst their pursuit of success.

4 - The Individualist:

Type Four individuals are introspective, creative, and emotionally expressive. They possess a rich inner world and are attuned to their emotions, often seeking authenticity and depth in their experiences and relationships. While they are capable of profound insights and artistic expression, they may grapple with feelings of melancholy, longing, or inadequacy.

5 -The Investigator:

Individuals embodying this type are analytical, perceptive, and intellectually curious. They seek knowledge, understanding, and autonomy, often withdrawing into solitude to explore complex ideas and theories. While they excel in problem-solving and critical thinking, they may struggle with emotional detachment and social engagement, preferring intellectual pursuits over interpersonal connections.

6 - The Loyalist:

Type Six individuals are loyal, responsible, and security-oriented. They value safety, stability, and preparedness, often seeking guidance and reassurance from trusted authorities or systems. While they are vigilant and conscientious, they may experience anxiety, scepticism, or indecision, grappling with doubts and uncertainties about the future.

7 - The Enthusiast:

Individuals of this type are spontaneous, optimistic, and adventurous. They are drawn to novelty, excitement, and pleasure, often seeking to avoid pain or discomfort through distraction or escapism. While they are charismatic and vivacious, they may struggle with impulsivity and commitment, chasing after new experiences without fully engaging with their emotions or responsibilities.

8 - The Challenger:

Type Eight individuals are assertive, independent, and protective. They possess a strong sense of justice and integrity, often advocating for the underdog or confronting injustice head-on. While they are courageous and resilient, they may struggle with vulnerability and intimacy, fearing weakness or betrayal in themselves or others.

9 - The Peacemaker:

Individuals embodying this type are easy-going, empathetic, and harmonious. They value peace, unity, and consensus, often seeking to mediate conflicts and maintain stability in their relationships and environments. While they are supportive and empathic, they may struggle with assertiveness and self-assertion, avoiding conflict or confrontation to preserve the status quo.

What value does the enneagram hold?

Although the enneagram is riddled with a plethora of limitations, for instance, pseudoscientific elements due to its spiritualist roots, subjectivity, lack of empirical evidence and a lack of standardised psychometric properties, it can certainly be a profoundly impactful catalyst in the journey of self-awareness and understanding.

All of us have underlying unconscious values regarding ourselves, which determine our problems, which therefore determines quality of life. Some root values can be of great power and be an instrumental tool in our own development as individuals, while others can conversely have the opposite and be detrimental to our wellbeing and ways of living (this is something that I will additionally explore within a future article). The enneagram has a place of great value here as it can begin the process of cultivating awareness of our own root beliefs, due to the nature of a core desire and fear being assigned to each type. Henceforth, despite the limitations surrounding the enneagram, its unorthodox nature allows us to develop a potentially more complete picture of our identities, placing great emphasis upon developmental aspects that can ultimately catalyse the process of our own growth and self-understanding.

Further exploration into personality

Now we have covered the three most well-known personality testing systems, we’ll continue by delving into some questions involving how our personalities are formed, how they change and more.

How are our personalities formed?

Within psychology, a vital debate is that of nature vs nurture – the extent to which human behaviour is a product of genetics or environment. Within the study of personality, an interactionist approach is taken (a combination of both/middle ground) with an estimated 20-60% of our personality being genetically influenced, the rest being determined by our environment. This has been proved to be the case through Twin and adoption studies, which have provided evidence for the heritability of traits such as temperament, which forms the foundation of personality development. Genes influence traits such as temperament, behavioural tendencies, and predispositions to certain psychological characteristics, which interact with environmental influences to shape personality.

The early years of life, particularly infancy and childhood, are crucial for personality development. Interactions with caregivers, family dynamics, and early experiences shape the development of attachment styles, social skills, and emotional regulation abilities. Positive experiences, such as secure attachment relationships and nurturing caregiving, can foster the development of trust, autonomy, and resilience, while adverse experiences, such as trauma or neglect, can lead to emotional and behavioural difficulties later in life. Furthermore, social dynamics in adolescence can additionally be a core aspect to personality development.

In addition, the different approaches within psychology have their own respective explanations to the formation of personality

The psychodynamic approach: Sigmund Freud proposed that personality arises from conflicts among the tripartite psyche: the id (unconscious instinctual drives), ego (conscious reality principle), and superego (internalised moral standards). Personality development occurs through psychosexual stages, where unresolved conflicts can lead to fixation and personality traits. For instance, a person with an oral fixation might exhibit traits such as dependency or passive-aggressiveness due to unresolved conflicts during the oral stage of development (age 0-1).

Biological: Places focus upon the biological underpinnings of individual differences in behaviour, cognition, and emotion, emphasising the role of genetics, brain structure and function, neurotransmitters, hormones, and other biological factors in shaping personality traits. Aforementioned biological studies and influences of dopamine and neural correlates are indicative features of this approach, while differences in hormones of testosterone in men and oestrogen in females give explanation into personality differences due to sex, as men in average tend to have higher levels of aggression (a facet of neuroticism) and lower agreeableness.

Humanistic approach: Maslow and Rogers emphasised the role of subjective experiences, self-concept, and personal growth in shaping personality, believing individuals have an innate drive towards self-actualisation, fulfilment, and becoming their best selves. A person who experiences congruence between their ideal self (who they aspire to be) and actual self (how they perceive themselves) is more likely to progress through the hierarchy of needs and thus have a greater likelihood of positive self-concept and healthy personality.

Behaviourist approach: revolves around observable behaviours and the influence of learning experiences, reinforcement, and operant/classical conditioning on personality development. Personality is seen as a collection of learned habits and responses to environmental stimuli. Positive reinforcement in response to acts of kindness and empathy may result in an increase in an individual’s agreeableness, while negative reinforcement through punishment of maladaptive behaviours in academic institutions or the workplace can cause an increase in conscientiousness.

Cognitive approach: based upon the view of the human mind being akin to a computer, with an input, processing, and output, attempting to infer unconscious mental processes. Thus, prioritising the role of thought processes, beliefs, perceptions, and schemas in shaping personality. They explore how individuals' interpretations of events influence their behaviour and emotional responses. As an example, a person with an optimistic explanatory style (attributing positive events to internal, stable, and global factors) is more likely to exhibit traits such as low neuroticism and high extraversion.

Therefore, although the combination of your parent’s personalities create the blueprint to your personality, our personality, just like our brains are ever-changing and malleable due to the events that occur within our lives and the choices we ourselves make in response to these.

Does personality change as we age?

On a societal level, it has been observed that as we age, our personality traits do in fact change, and in the same way for the vast majority of us. As we progress through life, our conscientiousness increases, neuroticism and extraversion decrease, while openness and agreeableness do not appear to show any positive or negative correlation – either remaining stable or fluctuating.

Of course, these changes will not be linear throughout our lifetime. When we face personal turmoil within our lives, we may become less agreeable due to a distrust of others – having a cognitive bias that results in a negative perception of others, while engaging more with the world and drawing ourselves away from conventionality in our daily habits, conversations and overall state of being opens the possibility for increased openness to experience. Any experience we face as we move through life – positive or negative, no matter how small – has the capacity to alter our personality. We are always changing, and none of us as individuals are ever in stasis, and this is what enables us to grow into the best manifestations of ourselves.

To what extent are the personalities people portray socially genuine manifestations of themselves?

The extent to which the personalities people portray socially reflect genuine manifestations of themselves can vary significantly depending on various factors such as context, social norms, individual psychological makeup, and situational demands. In many social interactions, individuals may present themselves in a way that aligns with societal expectations or norms, which may not always fully represent their true thoughts, feelings, or personality traits. This can occur for various reasons, including the desire to conform, avoid conflict, or create a favourable impression. For example, someone may act more extroverted at a party to engage with others and appear sociable, even if they are naturally more introverted.

In addition, individuals may also adjust their behaviour based on the specific social context or situation they are in. They may emphasise certain aspects of their personality while downplaying others depending on the people they are interacting with, the environment they are in, or the goals they hope to achieve. For instance, someone may act more assertive and confident in a professional setting to assert leadership, while being more relaxed and easy-going in a casual social gathering. However, despite the tendency to adapt behaviour in different social situations, there are also instances where individuals may genuinely express aspects of their true selves. In close relationships or with trusted friends, people may feel more comfortable being authentic and revealing their true thoughts, emotions, and personality traits. These genuine expressions of self can provide insight into an individual's core values, beliefs, and identity.

Overall, the extent to which the personalities people portray socially align with their genuine selves can vary depending on a multitude of factors, including social context, individual preferences, and situational demands. While social interactions may involve some level of adaptation or performance, genuine expressions of self can still occur in authentic relationships and meaningful connections, and we can all gain a level of integration into any aspect of our personal lives if we feel comfortable to do so.

Are certain types of personality more beneficial for certain career paths?

This is a highly debated and nuanced topic of discussion, and there is no true one size fits all answer to this question. Generally speaking, individuals with certain traits and scores on systems such as the big-5 may find certain career pathways will come more or less naturally than others, though you will find that there is an extremely wide array of personality traits in any workplace environment, but certain environments can demand exaggeration or underplaying of certain characteristics.

If we take the role of a police officer as an example, individuals in this role are required to be proficient in a multitude of aspects, including strong communication, problem-solving, critical thinking, ethical decision-making, emotional intelligence, teamwork and resilience. Police officers must be able to interact with the public, handle complex situations, make sound judgments, uphold ethical standards, maintain physical readiness, connect with diverse populations, utilise technology, and manage the physical and emotional demands of the job. Henceforth, a personality profile of ENTJ 1w2 126 and with high extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness and low neuroticism and openness may find a considerably innate ability in navigating the role of a police officer.

Regardless of the fact that certain personality aspects can be beneficial to developing proficiency in any occupational role, all individuals have the capacity to excel in their chosen fields regardless of their personality. The combination of the demands of a given job, paired with consistent effort over time will ultimately enable individuals to excel in their chosen line of work.

Can you change your personality?

Though genetics and early life experiences shape our personalities to some extent, we possess the power to actively alter certain facets of who we are. By engaging in introspection, seeking therapy, pursuing education, and honing our skills through consistent practice, we can initiate profound changes in our behaviour and cultivate traits that resonate with our aspirations and principles. One vital aspect to this can be a consistent daily practice of journaling, reflecting on your thoughts, feelings and emotions throughout the day, and evaluating your daily activities to develop a sense of congruence between your current sense of self and the person that you desire to be. A mentality that is of great value in this manner of continuous growth is to remember that you are already perfect as you are, but you can always continue to refine yourself and your way of being – striving to better yourself and subsequently the lives of those around you in whatever feels most authentic to you.

Conclusion

The subject of personality has developed drastically since its inception with Hippocrates’ theory of the 4 temperaments in 370BC, with five factor models such as the big-5 currently being the most scientifically valid with our current psychological knowledge and understanding of human personality, offering nuanced insight to the complexity of this field of study. As psychological theories and studies continue, we will progressively move closer to developing a more universal understanding of the intricacies of the operations of the human psyche, the HEXACO model, with its added dimension of honesty-humility being a prime example of this. Yet, personality remains a dynamic and multifaceted aspect of human experience, shaping our behaviours, relationships, and life outcomes.

The study of personality offers a plethora of beneficial applications to our everyday lives. It enables the catalysing of the trajectory of self-awareness and growth by allowing us to make informed decisions through identifying areas for growth, increasing the quality of our interpersonal relationships via the cultivation of empathy, communication and conflict-resolution through a more extensive understanding of those within our lives, in addition to applications in the workplace and education. Understanding our own respective identities thus yields great value, maximising our potential and ultimately allowing us to live a life of increased fulfilment, and therefore the lives of those around us.